This article is part 2 of 2. Read part one here: What Is A Preferment?

Various Types of Preferments

Preferments can go by many different names including chef, levain, sponge, madre bianca, mother, biga and poolish. But in my opinion, there are three major approaches to preferments that will encompass all others, much like classic French sauces are mostly derivatives from the Five French Mother Sauces. To help you better understand the three major approaches to preferments, I give you the “Three Mother Preferments” (somewhere out there, a French Baker just face palmed himself, and my life is now complete). These three “mother preferments” are poolish, biga and pâte fermentée.

Poolish Preferment

Sometimes referred to as a sponge or barm (although a barm is more technically a natural levain or sourdough starter), tradition has it that the term “Poolish” comes from Polish baker’s in Vienna who developed the technique of prefermentation, later adopted by French bakers. And although I’m always eager to annoy French baker’s and chefs, there really is no solid, historical evidence of where the term “poolish” originated.

What we can agree on however is the poolish style preferment is the most common approach used by enthusiasts and professional bakers alike, mainly because it’s high hydration allows the yeast to propagate at a constant pace, and it’s incredibly easy to apply a preferment to any bread recipe since it contains a 1:1 ratio of flour and water (which makes final bread dough calculations intuitive, especially when converting various bread recipes that don’t utilize a preferment).

Based on the baker’s percentage, a poolish starter will have 100% hydration and .2% yeast (always based on the flour’s weight).

This means the basic formulation for a poolish preferment is:

*Because cake yeast (commonly only found in professional bakeries) is less dense with yeast microbes than active or instant dry, you can up the percentage to 1% to get the same results.

Now I do realize this seems like a lot of preferment for the home baker, and it is, but using these numbers you can at least visualize the ratios through the baker’s percentage. If you want to make a smaller poolish preferment and don’t have a gram scale accurate to the 10th of a gram, then a simple, one finger pinch of yeast will do. For example, if I was making a preferment for one or two loaves of bread, it would probably look something like this:

-

200g Flour

-

200g Water

-

Pinch Yeast

Once mixed, a poolish style preferment will be ready to use in about 12-18 hours, assuming an ambient room temperature of 68-72°F/20-22°C and your yeast usage doesn’t exceed .2% based on the flour’s weight. Remember, the more yeast used and the hotter your room temperature, the sooner your preferment will be ready (which isn’t necessarily desirable since the whole purpose of a preferment is to slow down the fermentation process). For every 17°F/9°C your room temperature raises or drops, the yeast activity will be doubled or cut in half, taking the yeast half the time or twice the time respectively to achieve the same amount of fermentation.

For more information on incorporating a poolish style preferment into your bread doughs, please see “The Basics of Using a Preferment” at the end of this article.

Biga Preferment

This style of preferment was developed by Italian bakers, and in Italy, a Biga refers to any style of preferment that contains flour, water and yeast, no matter the percentages. However, it’s more common for a Biga to have less hydration than a poolish. For the sake of understanding various approaches to preferments, Biga’s are low hydration (stiffer) and take longer to finish fermentation as compared to a poolish containing the same percentage of yeast. This is because yeast’s movement is impeded by lower hydrations, taking them longer to propagate and consume all the starches contained within the bread dough.

This is why Biga Preferments will usually, but not always, contain more yeast based upon the flour’s rate (about 1%) than a wetter style of preferment like a poolish. At the one percent use rate, a biga preferment left at a standard room temperature will be ready to use in about 14-18 hours. The basic formulation for a biga starter is:

-

500g Flour - 100%

-

300g Water - 60%

-

5g Yeast - 1%

While this is a common formulation for a biga starter, the yeast percentage and hydration rate can vary depending on the baker and the final application of the preferment. However, in the spirit of separate approaches, low hydration starters will take longer to ferment than a poolish, which is why the yeast percent is raised to 1% for the former instead of .2% for the latter.

Anecdotally speaking, this stiffer dough can stand up to longer fermentation times, especially if the yeast percent is lowered, creating more complex flavors via acetic and latic acid production, the same acids responsible for sourdough’s complex flavor and aroma.

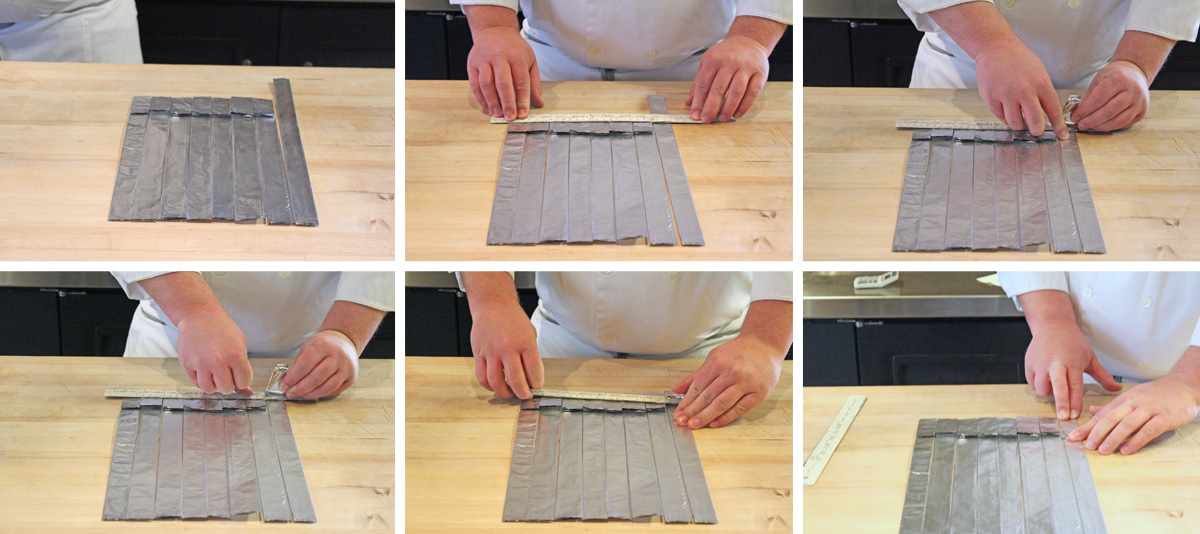

Once a biga preferment is airy and full of life (and expanded by about double it’s original volume), it can then be incorporated into the final dough formulation by cutting into small pieces, mixed with the rest of the recipe’s liquid, and then incorporated into the remaining ingredients. This will ensure an even dispersion of yeast contained in the preferment, resulting in better bulk fermentation and proofing.

Pâte Fermentée (Chef, Old Dough)

The “old dough” or pâte fermentée style of preferment is extremely convenient if you’re baking the same bread recipe on a regular basis. This approach was championed by famed French baker Raymond Cavell who credited this method with adding complexity of flavor and increased oven spring to his world famous baguettes.

The basic concept is simple; up to 1/3 of bread dough is reserved after the bulk fermentation to levin the next batch of bread. So in the case of a classic baguette, the first time the recipe is made, flour, water, yeast, and salt will be mixed together and allowed to bulk ferment.

After the bulk fermentation is complete, the dough is punched down, one third is reserved to levin the next batch of bread, while the rest of the dough is scaled, formed, proofed, and baked.

This old dough can be stored for about 8-12 hours at room temperature or retarded in the refrigerator for up to 3 days. It can also be frozen for up to 6 months, removing from the freezer and allowing to thaw fully (about 12-16 hours at room temperature, (24-36 hours in the fridge depending on the dough's volume) before using it to levin a batch of bread.

The Basics of Using a Preferment

Now that you understand what a preferment is, why they’re beneficial to bread baking, and the three major approaches, let’s talk about how to actually apply this knowledge to any bread recipe.

In general, 1/4 to 1/2 of a bread recipe’s total flour will be used to create a preferment. The amount of liquid depends entirely on what approach you’re using from above (low hydration biga, high hydration poolish, or pâte fermentée).

The amount of pre-ferment used will depend on how long you want the bulk fermentation process to take, after it's incorporated into the the rest of the ingredients. In general, when half of the dough's flour comes from a preferment, you can count on a 2-4 hour bulk fermentation and a 1-2 hour proof.

Let's use our basic baguette recipe to put this into perspective:

The original recipe uses the direct method, meaning the ingredients are mixed together, allowed to bulk ferment, shaped, proofed and baked (scalable recipe - video recipe).

To add extra complexity of flavor, we’ll remove half of the recipe’s flour and create a poolish style preferment, transforming our recipe into something like this:

Preferment

-

400g Flour

-

400g Water

-

Pinch Yeast

Mix ingredients together, place in a container large enough to allow the preferment to at least double in size, and allow to ferment at room temperature (68-72°F/20-22°C) for 12-16 hours (or retard in fridge for up to 3 days).

The next day, mix the preferment with the remaining ingredients:

-

400g Flour

-

120g Water

-

16g Salt

Follow the baguette recipe as normal. Remember, your bulk fermentation and proofing stages might take a little longer than normal, about 3 and 2 hours respectively, but your patience will be rewarded with a superior baguette. Obviously the fermentation can be delayed further by using less preferment, retarding the bread during bulk fermentation or proofing, or all of the above. Again, the longer the fermentation and proofing process, the more complex the bread will be, until the yeast consume all the available food, causing them to die.

To convert the above baguette recipe for use with a biga style starter:

Mix ingredients together until they form a shaggy dough. Leave at room temperature and allow to ferment for 14-18 hours (or retard in fridge for up to 3 days).

The next day, mix with:

-

400g Flour

-

280g Water

-

16g Salt

Once ingredients are kneaded together, follow the baguette recipe as normal, with the expectation of your bulk ferment and proofing stages taking a little longer.

To use the pâte fermentée method, you can simply reserve 1/3 of the baguette dough recipe, but this will also decrease the overalll yield. If you want to have the same yield every time (4 baguettes), then scale each ingredient by 1.5. For example, our above baguette recipe adds up to 1336g total dough weight. Here's how the math looks

800g X 1.5 = 1200g Flour

520g X 1.5 = 780g Water

16g X 1.5 = 24g Salt

7g X 1.5 = 10.5 Yeast

_____________________________________

1336g X 1.5 = 2004g Total Dough Weight

So as you can see from the above example, scaling any bread recipe by 1.5 will allow you to remove 30% of the dough to be used as a preferment in your next batch, while resulting in the same total yield from bake to bake. Even though 1/3 is technically 33%, scaling a recipe by 1.5 and then removing .3 is easy to remember, keeps your numbers round, and the extra 3% is negligible.

The portion of the dough removed can be stored at room temperature if you plan on baking the same bread in the next 12-18 hours, in the fridge up to 3 days, or the freezer for up to 6 months.

The final baguette recipe would be:

-

668g Pâte Fermentée (Old Dough)

-

800g Flour

-

520g Water

-

16g Salt

-

Yeast - Optional, depending on how fast you want the bread to rise, or how avtive your old dough looks. If it's a little past it's prime or you want a faster, more dependable rise, add 7g of yeast.

You might also be interested in the following:

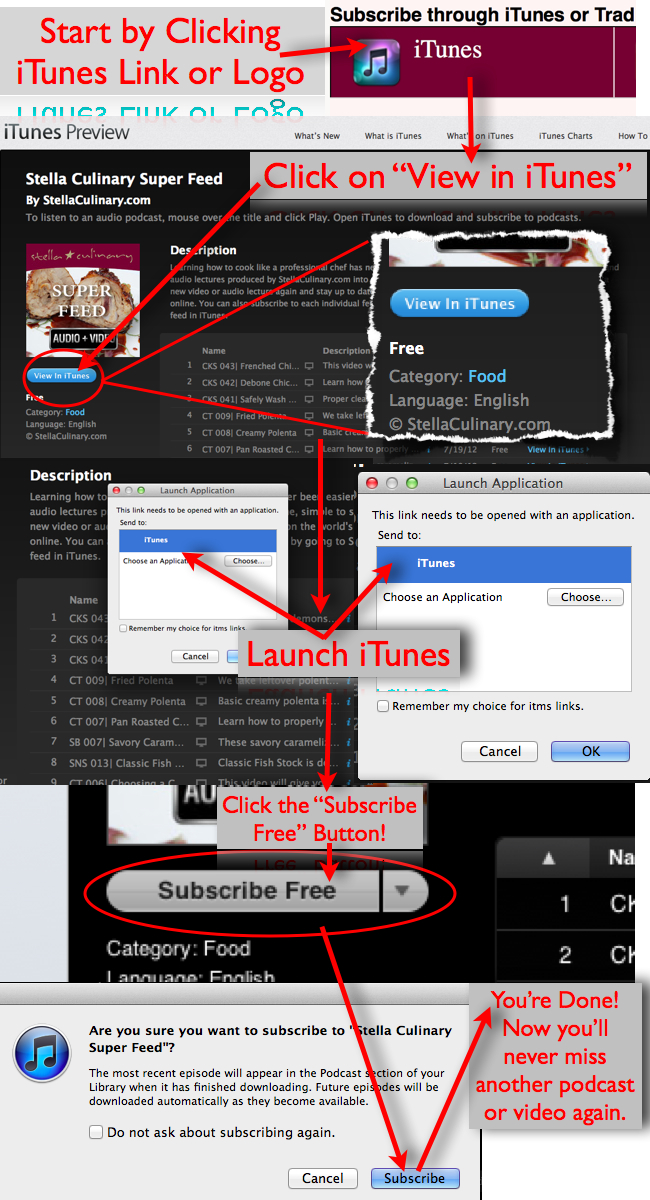

Podcast Episodes

Videos - Visit Our Bread Baking Video Index

For this month's Stella Culinary Cooking Challenge, I wanted to get back to basics, focusing on a couple simple techniques, and reinforcing the skill set of separating flavor structure from technique.

For this month's Stella Culinary Cooking Challenge, I wanted to get back to basics, focusing on a couple simple techniques, and reinforcing the skill set of separating flavor structure from technique.